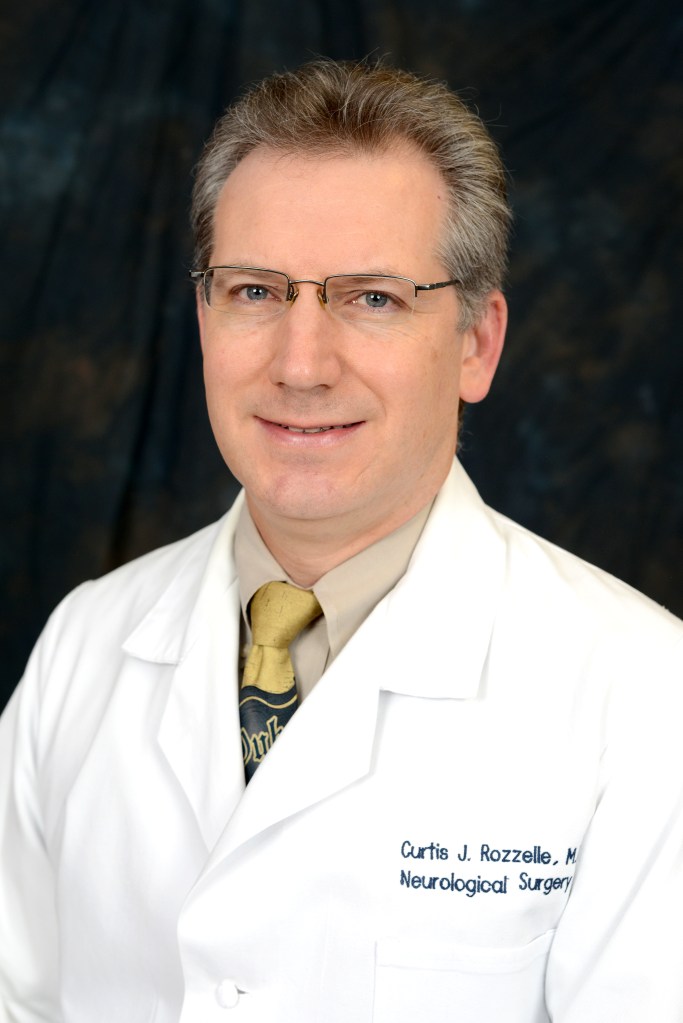

ECMO in use at Children’s of Alabama (file photo)

Almost a decade ago, Nephrology specialists at Children’s of Alabama embarked on a journey to improve outcomes in neonates with severe congenital kidney disease by adapting the Aquadex machine, a small extracorporeal circuit used for adults with heart failure. Traditionally, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was deemed unsuitable for this population due to perceived nonviability. In 2016, at the family’s request, a baby with severe congenital kidney failure and severe respiratory failure was placed on ECMO to be given a chance at life. The baby also required kidney support therapy (KST) to survive. After receiving a kidney transplant at age 2, the child now goes to school, plays sports, sings and dances.

Since 2016, of the 31 neonates with congenital kidney failure who were admitted to the Children’s neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), five required ECMO support and KST in the first two weeks of life. In February 2024, Kara Short, MSN, CRNP, CPNP-PC, David Askenazi, M.D., MSPH, and others published a case report in Pediatrics, highlighting the complex treatment of the five babies and the journey to NICU discharge for the four survivors. This study challenges the previous norms and conventions that these babies had no chance at life.

Congenital kidney failure poses unique challenges to neonates, affecting not only renal homeostasis but also respiratory integrity. Diagnoses among the five patients in the study included posterior urethral valves, bilateral renal dysplasia and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Despite gestational age ranging from 35.6 to 37.1 weeks and birth weight from 2,740 grams to 3,140 grams, all five patients received KST by postnatal day seven. Additionally, they were all placed on ECMO within the first nine postnatal days due to severe respiratory distress after being unresponsive to conventional interventions.

Four of the five patients survived and are thriving today. Pulmonary hypertension resolved in each survivor, with three requiring no oxygen support and one needing only nocturnal oxygen. Three survivors underwent successful kidney transplants, while one awaits transplant evaluation. This challenges the traditional notion of reflexively assigning nonviability to neonates with congenital kidney failure and severe pulmonary complications.

This research highlights the significance of ECMO and kidney support therapy in mitigating the adverse effects of pulmonary edema, uremia and electrolyte complications. The use of a filter through the ECMO circuit—to perform continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD), continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH) with the Aquadex machine, peritoneal dialysis and intermittent hemodialysis—showcases the synergism and need for different approaches to manage these complex cases.

Managing congenital kidney failure requires a multidisciplinary approach involving neonatology, nephrology, surgery and multiple ancillary divisions. “As healthcare providers, we all bring something to the table,” Askenazi said. “The families need clear, concise information so they can understand their options when making treatment decisions. Our job is to develop programs, systems and plans to help those kids have the best chance at life.”

The families of the neonates faced challenging decisions, including the choice of full medical support or palliative care. Despite the complexity and potential extended NICU stay, all five families opted for full medical support. Clear communication, counseling and informed decision-making were instrumental when families made medical decisions about their baby’s care.

The successful outcomes of neonates with congenital kidney failure undergoing ECMO challenge previous assumptions of nonviability. Meticulous ECMO, respiratory, nutritional and kidney support therapies are essential to favorable long-term results. Further investigation is needed to define the optimal strategies to improve outcomes in severe congenital kidney disease cases. “We want to share this information with other programs to let them know that these kids have a chance at life; what we learned in this very small cohort is that these lungs can develop and grow if given a chance,” Short said.

“When thinking about the future, we’re asking ourselves: How can we get the very best technology to care for these babies? How can we help other programs improve so they can better care for their kids? How do we ensure that families are counseled with all viable options in an honest and comprehensive way?” Askenazi said. “We will continue to make progress. We have recently received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to partner with industry to make a better device for neonates. We recognize that we must continue to educate our colleagues across the U.S. and the world about what we have learned from these miracle babies.”